AASCU’s Millennium Leadership Initiative plays a key role in training underrepresented higher ed leaders.

A small but committed group of Black and African American higher education leaders had a simple but powerful concept in 1998: to create a professional development program that would motivate, shape and diversify current and aspiring college presidents and chancellors. That idea ultimately would become the genesis for the prestigious Millennium Leadership Initiative (MLI), an American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU) program.

Since its launch more than two decades ago, college presidents and chancellors across the country have worked tirelessly to serve as mentors, speakers and coaches for those traditionally underrepresented in the highest ranks of higher education. The support stemming from the MLI, which remains one of AASCU’s premier leadership development experiences, is designed to provide new opportunities for emerging postsecondary leaders, creating a more intentional pipeline to the college presidency.

Indiana University’s connection to the MLI is a longstanding one. Two of the MLI’s founding members have ties to IU. Professor Emeritus Charlie Nelms, Ed.D., is a former vice president at IU Bloomington and chancellor at IU East. F.C. Richardson, Ph.D., is a former dean at IU Northwest and chancellor at IU Southeast and was the first African American to serve in such a position on any IU campus. Richardson created the mentor component integral to MLI and all AASCU leadership development programs that followed.

In addition, Ken Iwama, J.D., who serves as chancellor of IU Northwest and is a 2014 graduate of the MLI program, has now been asked to serve on the national executive steering committee for the Millennium Leadership Initiative.

Iwama believes his work with the MLI will ultimately benefit IU and IU Northwest. “Everything is connected,” he said. “There are a lot of parallels between MLI and what we do at IU Northwest by developing the leaders of tomorrow.”

Diversifying the College Presidency

The need for change in diversifying the college presidency was the impetus for the creation of the MLI. Today, that mission remains by ensuring new generations of leaders in higher education reflect the changing demographics of today’s college students and the population at large.

Nelms recalls the deficit of diverse talent when he was named chancellor of IU East in 1987.

“Prior to the Equal Employment Opportunity/Affirmative Action era, which began gaining significant traction in the 1970s, higher education faculty and leadership ranks were overwhelmingly white and male. Few Black faculty and administrators, for example, could be found outside of the 107 historically Black colleges and universities, 95 percent of which were in the South,” he explains.

Moreover, most higher education associations, including the American Council on Education and the American Association of Higher Education, were led by white men and co-located in Washington, DC, Nelms notes.

According to Nelms, these organizations controlled everything related to higher education. In addition, these leaders served as keynote speakers and panelists at their annual national meetings. Occasionally, he said, a high-profile female or Black person would be invited to speak.

This reality prompted a handful of Black and African American activists, junior-level administrators and faculty at predominantly white institutions (PWIs) to come together and form the Black Caucus of the American Association of Higher Education, or AAHE.

Its creation led to an immediate increase in the diversity among the presenters, with Black Caucus members leading the charge. Nelms says many members of that group would go on to become members of the executive leadership team at PWIs.

The action of the AAHE Black Caucus put pressure on other associations to change their way of programming, and, in a few years, change began to happen.

Establishment of the MLI

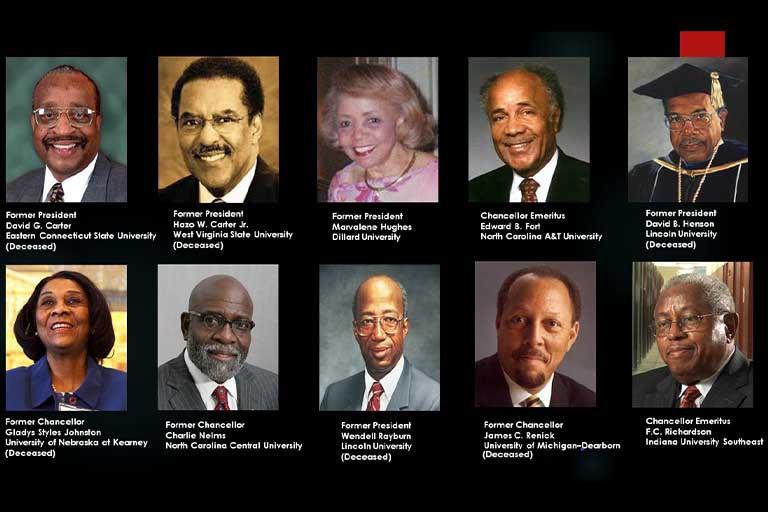

To launch MLI, the 10 founders contributed $5,000 from their institutional budgets and volunteered as MLI faculty and mentors. Sessions included finance, strategic planning, fundraising, lobbying, and governance, among other topics. In addition, one of the founders volunteered to serve as executive director, and it was not until many years later that a part-time executive director officially came on board.

Following the successful launch of the MLI in 1999, efforts were made to connect with all AASCU presidents and to encourage their support. As a result, the small group quickly grew from 10 supporters to 40, to more than twice that number today.

Nelms came up with the idea for naming the program the “Millennium Leadership Initiative.” He describes his vision this way, “Millennium is both a recognition of the change to a new century and the importance of having leaders who are prepared to be agents of change through educational leadership.”

Both Nelms and Richardson remain enthusiastic about the MLI. Since the inaugural MLI class of 1999, 694 individuals have graduated from the program. More than one in five individuals have achieved the position of chancellor or president, and 153 graduates have become first-time college and university presidents. Forty hold multiple presidencies and chancellor positions.

The MLI Experience

The concept of the MLI is to help those who aspire to become a college president or chancellor. A comprehensive suite of support—from intensive mentoring to networking and advising—facilitates this process, helping individuals enhance and elevate their leadership abilities and skills development.

From its inception, MLI was designed to reinforce the vital role that diversity plays as part of the institutional mission at a college or university. Harnessing the potential of untapped talent and providing the tools to enhance that talent continues to be the goal of the MLI, with a focus on individuals who commit to equity, diversity and inclusion. This includes Blacks and African Americans, Hispanics, women, Asian Americans and others.

A selection committee made up solely of presidents and chancellors administer the rigorous application and admissions procedure for participants in the MLI. In addition, the MLI Institute’s presidential faculty and other professionals offer their expertise and insight on various leadership-related topics and provide training in those areas.

After the Institute, graduates are assigned a mentor and a coach from a volunteer group of presidents and chancellors whose role is to provide career guidance and assist participants, known as “protégés,” in the subsequent phases of their careers.

A vital part of these one-on-one interactions involves frank discussions with the presidents and chancellors, who assess the professional development plans developed by the protégés. The dialogue is an integral component of the MLI, providing feedback and invaluable support from individuals who can speak to the challenges and opportunities facing university presidents and chancellors today.

Richardson, credited for founding the mentoring program and serving as committee chair from 1999-2013, said, “MLI is deeply committed to ensuring every participant has a mentor, giving protégées the benefit of their experience. In many cases, these pairings become life-long relationships.”

Mildred García, Ed.D., president of the American Association of State Colleges and Universities, still finds the impact of the MLI and the lessons she learned from the program beneficial today.

“One of the most important things about the program is being a protégé. What I loved about the effort is not just the skills and competencies created or the expertise needed to move forward, but rather that I learned what it would be like as a single female Latino to be a president or chancellor,” explains García. “I learned about the many demands and what it would take to be successful from a professional, academic and personal standpoint. That is invaluable.”

Moving forward, García firmly believes in the enduring value of MLI and its work to diversify today’s higher education landscape.

Nelms echoes those sentiments.

“I consider my participation in the founding of MLI among the most significant activities of my 50-year career in higher education. Even in retirement, I remain engaged in the life of the program as a mentor and advisor for aspiring presidents. In addition, in recognition of the importance of executive coaching in presidential success, my wife, Jeanetta, and I have established an endowed fund through MLI to provide coaching to a protégé appointed to the presidency,” he says.